Do I Have to Again Take Birth After the Universe Is Recreated

Hindu cosmology is the description of the universe and its states of thing, cycles within fourth dimension, concrete structure, and effects on living entities according to Hindu texts.

Thing [edit]

All thing is based on 3 inert gunas (qualities or tendencies):[1] [2] [3]

- sattva (goodness)

- rajas (passion)

- tamas (darkness)

There are 3 states of the gunas that make up all affair in the universe:[1] [3] [4] [5] [vi] [vii]

- pradhana (root matter): gunas in an unmixed and unmanifested state (equilibrium).

- prakriti (fundamental thing): gunas in a mixed and unmanifested land (agitated).

- mahat-tattva (matter or universal womb): gunas in a mixed and manifested state.

Pradhana, which has no consciousness or will to act on its ain, is initially agitated by a fundamental want to create. The different schools of thought differ in understanding about the ultimate source of that want and what the gunas are mixed with (eternal elements, time, jiva-atmas).[8] [9]

The manifest material elements (affair) range from the about subtle to the most physical (gross). These fabric elements comprehend the individual, spiritual jiva-atmas (embodied souls), allowing them to interact with the cloth sense objects, such as their temporary cloth bodies, other witting bodies, and unconscious objects.

Manifested subtle elements:[x] [11] [12] [a]

- ahamkara (ego)

- buddhi (intelligence)

- citta (mind)

Manifested physical (gross) elements (a.yard.a. pancha bhoota or 5 smashing elements) and their associated senses and sense organs that manifest:[xiii] [14] [xv] [a]

- space/ether > audio > ear

- air > odour > nose

- burn down > sight/grade > center

- h2o > taste > tongue

- earth > bear on > pare

Time [edit]

Time is infinite with a cyclic universe, where the current universe was preceded and volition exist followed by an infinite number of universes.[16] [17] The different states of matter are guided by eternal kala (time), which repeats general events ranging from a moment to the lifespan of the universe, which is cyclically created and destroyed.[18]

The earliest mentions of cosmic cycles in Sanskrit literature are found in the Yuga Purana (c. 1st century BCE), the Mahabharata (c. tertiary century BCE – quaternary century CE), and the Manusmriti (c. second – 3rd centuries CE). In the Mahabharata, at that place are inconsistent names applied to the wheel of creation and destruction, a name theorized every bit still being formulated, where yuga (generally, an age of fourth dimension)[19] [20] and kalpa (a day of Brahma) are used, or a 24-hour interval of the Brahma, the creator god, or but referred to every bit the process of creation and destruction, with kalpa and day of Brahma becoming more than prominent in afterward writings.[21]

Prakriti (primal matter) remains mixed for a maha-kalpa (life of Brahma) of 311.04 trillion years, and is followed by a maha-pralaya (slap-up dissolution) of equal length. The universe (affair) remains manifested for a kalpa (mean solar day of Brahma) of 4.32 billion years, where the universe is created at the start and destroyed at the end, only to be recreated at the start of the adjacent kalpa. A kalpa is followed by a pralaya (partial dissolution, a.chiliad.a. night of Brahma) of equal length, when Brahma and the universe are in an unmanifested state. Each kalpa has xv manvantara-sandhyas (junctures of keen flooding) and 14 manvantaras (age of Manu, progenitor of mankind), with each manvantara lasting for 306.72 million years. Each kalpa has 1,000 and each manvantara has 71 chatur-yugas (epoch, a.k.a. maha-yuga), with each chatur-yuga lasting for 4.32 million years and divided into 4 yugas (dharmic ages): Satya Yuga (i,728,000 years), Treta Yuga (1,296,000 years), Dvapara Yuga (864,000 years), and Kali Yuga (432,000 years), of which we are currently in Kali Yuga.[22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29]

Life [edit]

The individual, spiritual jiva-atma (embodied soul) is the life force or consciousness inside a living entity. The jivas are not created, and are distinctly different from the created unconscious affair. The gunas in their manifest country of matter, comprehend the jivas in various ways based on each jiva's karma and impressions. This material covering of matter allows the jivas to interact with the material sense objects that make upwardly the material universe, such as their temporary fabric bodies, other conscious bodies, and unconscious objects.[30] [31] [32]

The textile creation is called maya ("that which is non") due to its impermanent (not-eternal), temporary nature of sometimes being manifest and sometimes not. It has been compared to a dream or virtual reality, where the viewer (jiva) has real experiences with objects that volition eventually get unreal.[33] [34]

Through these interactions, a jiva starts to identify the temporary material body as the true self, and in this way becomes influenced and bound past maya perpetually in a conscious state of nescience (ignorance, unawareness, forgetfulness). This conscious state of nescience leads to samsara (cycle of reincarnation), simply to cease for a jiva when moksha (liberation) is achieved through self-realization (atman-jnana) or remembrance of i's true spiritual self/nature.[35] [36] [37] [38] [39]

The different schools of idea differ in understanding about the initial event that led to the jivas entering the cloth creation and the ultimate state of moksha.

Creation and structure [edit]

Hinduism is a conglomeration/group of distinct intellectual or philosophical points of view, rather than a rigid common set of beliefs.[40] Information technology includes a range of viewpoints about the origin of life. There is no single story of cosmos, due to dynamic diversity of Hinduism, and these are derived from diverse sources like Vedas, some from the Brahmanas, some from Puranas; some are philosophical, based on concepts, and others are narratives.[41] Hindu texts do not provide a unmarried approved business relationship of the creation; they mention a range of theories of the creation of the earth, some of which are apparently contradictory.[42]

Rigveda [edit]

According to Henry White Wallis, the Rigveda and other Vedic texts are full of alternative cosmological theories and curiosity questions. To its numerous open-concluded questions, the Vedic texts present a multifariousness of idea, in verses imbued with symbols and apologue, where in some cases, forces and agencies are clothed with a distinct personality, while in other cases as nature with or without anthropomorphic activity such every bit forms of mythical sacrifices.[43]

Hiranyagarbha sukta (gold egg) [edit]

Rigveda ten.121 mentions the Hiranyagarbha ("hiranya = golden or radiant" and "garbha = filled / womb") that existed before the cosmos, as the source of the creation of the Universe, similar to the earth egg motif plant in the creation myths of many other civilizations.[44] Information technology states a golden child was born in the universe and was the lord, established earth and heaven, and so asks simply who is the god to whom we shall offer the sacrificial prayers?[45]

This metaphor has been interpreted differently past the various afterward texts. The Samkhya texts state that Purusha and the Prakriti fabricated the embryo, from which the globe emerged. In another tradition, the creator god Brahma emerged from the egg and created the earth, while in yet another tradition the Brahma himself is the Hiranyagarbha.[46] The nature of the Purusha, the creation of the gods and other details of the embryo creation myth have been described variously by the later Hindu texts.

Purusha Sukta [edit]

The Purusha Sukta (RV x.90) describes a myth of proto-Indo-European origin, in which the creation arises out of the dismemberment of the Purusha, a earliest cosmic beingness who is sacrificed by the gods.[44] [47] Purusha is described as all that has e'er existed and will ever exist.[48] This existence'south body was the origin of four different kinds of people: the Brahmin, the Rajanya, the Vaishya, and the Shudra.[49] Viraj, variously interpreted as the mundane egg[47] (see Hiranyagarbha) or the twofold male-female person energy, was born from Purusha, and the Purusha was built-in again from Viraj. The gods and so performed a yajna with the Purusha, leading to the cosmos of the other things in the manifested world from his various body parts and his mind. These things included the animals, the Vedas, the Varnas, the celestial bodies, the air, the heaven, the heavens, the world, the directions, and the Gods Indra and Agni.

The subsequently texts such as the Puranas identify the Purusha with God. In many Puranic notes, Brahma is the creator god.[50] : 103, 318 However, some Puranas also identify Vishnu, Shiva or Devi as the creator.[50] : 103

Nasadiya Sukta [edit]

The Nasadiya Sukta (RV x.129) takes a most-agnostic stand up on the creation of the primordial beings (such equally the gods who performed the sacrifice of the Purusha), stating that the gods came into being afterward the world'south creation, and nobody knows when the world first came into beingness.[51] It asks who created the universe, does anyone really know, and whether it can ever be known.[52] The Nasadiya Sukta states:[53] [54]

Darkness there was at first, by darkness hidden;

Without distinctive marks, this all was water;

That which, becoming, by the void was covered;

That Ane past force of heat came into being;Who really knows? Who volition hither proclaim it?

Whence was information technology produced? Whence is this creation?

Gods came after, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?Whether God'due south will created it, or whether He was mute;

Perchance it formed itself, or perhaps it did not;

Only He who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,

But He knows, or perhaps He does not know.

Other hymns [edit]

The early hymns of Rigveda besides mention Tvastar as the first built-in creator of the homo globe.[58]

The Devi sukta (RV 10.125) states a goddess is all, the creator, the created universe, the feeder and the lover of the universe;[59]

Recounting the creation of gods, the Rig Veda does seem to assert ''creatio ex nihilo''.[60] Rig Veda 10.72 states:[54] RV ten.72 states:

i. Now amid acclaim nosotros will proclaim the births of the gods,

and so that one in a afterwards generation will run across (them) as the hymns are recited.

2 The Lord of the Sacred Formulation [=Bhṛaspati] smelted these (births) similar a smith

In the ancient generation of the gods, what exists was born from what does not exist.

3 In the first generation of the gods, what exists was born from what does not be.

The regions of infinite were born following that (which exists)—that(which exists) was built-in from the one whose feet were opened upward.—Bṛhaspati Āṅgirasa, Bṛhaspati Laukya, or Aditi Dākṣāyaṇī, The Gods, Rig Veda 10.72.1-3[b]

RV i.24 asks, "these stars, which are assail loftier, and appear at night, whither do they go in the daytime?" RV x.88 wonders, "how many fires are at that place, how many suns, how many dawns, how many waters? I am not posing an awkward question for you fathers; I enquire you, poets, only to discover out?"[61] [62]

Brahmanas [edit]

![]()

The Shatapatha Brahmana mentions a story of creation, in which the Prajapati performs tapas to reproduce himself. He releases the waters and enters them in the form of an egg that evolves into the cosmos.[63] The Prajapati emerged from the aureate egg, and created the earth, the heart regions and the sky. With further tapas, he created the devas. He also created the asuras, and the darkness came into the existence.[50] : 102–103 It also contains a story like to the other great inundation stories. Later the great flood, Manu the only surviving human, offers a sacrifice from which Ida is born. From her, the existing human race comes into the being.[l] : 102–103

The Shatapatha Brahmana states that the current human generation descends from Manu, the but homo who survived a great deluge afterwards being warned by the God. This legend is comparable to the other flood legends, such as the story of the Noah's Ark mentioned in the Bible and the Quran.[64]

Upanishads [edit]

The Aitareya Upanishad (3.4.ane) mentions that just the "Atman" (the Self) existed in the beginning. The Self created the sky (Ambhas), the sky (Marikis), the earth (Mara) and the underworld (Ap). He and then formed the Purusha from the h2o. He also created the speech, the fire, the prana (breath of life), the air and the various senses, the directions, the trees, the mind, the moon and other things.[65]

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (one.4) mentions that in the beginning, only the Atman existed as the Purusha. Feeling lonely, the Purusha divided itself into 2 parts: male ("pati") and female ("patni"). The men were built-in when the male embraced the female. The female thought "how can he embrace me, afterwards having produced me from himself? I shall hibernate myself." She so became a moo-cow to hibernate herself, merely the male person became a balderdash and embraced her. Thus the cows were built-in. Similarly, everything that exists in pairs, was created. Next, the Purusha created the fire, the soma and the immortal gods (the devas) from his better part. He also created the diverse powers of the gods, the different classes, the dharma (law or duty) and then on.[66] The Taittiriya Upanishad states that the being (saturday) was created from the not-being. The Being later on became the Atman (2.7.1), and then created the worlds (1.ane.1).[50] : 103 The Chhandogya states that the Brahma creates, sustains and destroys the world.[67]

Puranas [edit]

An attempt to depict the creative activities of Prajapati; a steel engraving from the 1850s

The Puranas genre of Indian literature, establish in Hinduism and Jainism, contain a department on cosmology and cosmogony as a requirement. There are dozens of different Mahapuranas and Upapuranas, each with its own theory integrated into a proposed human history consisting of solar and lunar dynasties. Some are similar to Indo-European cosmos myths, while others are novel. Ane cosmology, shared past Hindu, Buddhist and Jain texts involves Mount Meru, with stars and sunday moving around it using Dhruva (North Star) equally the focal reference.[68] [69] According to Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, the diversity of cosmology theories in Hinduism may reflect its tendency to not reject new ideas and empirical observations as they became available, but to adapt and integrate them creatively.[70]

In the after Puranic texts, the creator god Brahma is described as performing the act of 'creation', or more specifically of 'propagating life within the universe'. Some texts consider him equivalent to the Hiranyagarbha or the Purusha, while others country that he arose out of these. Brahma is a part of the trimurti of gods that also includes Vishnu and Shiva, who are responsible for 'preservation' and 'devastation' (of the universe) respectively.

In Garuda Purana, there was zero in the universe except Brahman. The universe became an expanse of water, and in that Vishnu was born in the gilt egg. He created Brahma with four faces. Brahma then created the devas, asuras, pitris and manushas. He too created the rakshasas, yakshas, and gandharvas. Other creatures came from the various parts of his body (e.m. snakes from his hair, sheep from his breast, goats from his mouth, cows from his stomach, others from his feet). His body hair became herbs. The four varnas came from his trunk parts and the four Vedas from his mouths. He created several sons from his mind: Daksha, Daksha'southward wife, Manu Svaymbhuva, his married woman Shatarupta and the rishi Kashypa. Kashypata married thirteen of Daksha's daughters and all the devas and the creatures were born through them.[50] : 103 Other Puranas and the Manu Smriti mention several variations of this theory.

In Vishnu Purana, the Purusha is same as the creator deity Brahma, and is a part of Vishnu.[fifty] : 319 The Shaivite texts mention the Hiranyagarbha as a creation of Shiva.[46] According to the Devi-Bhagavata Purana Purusha and Prakriti emerged together and formed the Brahman, the supreme universal spirit that is the origin and support of the universe.[50] : 319

Brahmanda (catholic egg) [edit]

Co-ordinate to Richard 50. Thompson, the Bhagavata Purana presents a geocentric model of our Brahmanda (cosmic egg or universe), where our Bhu-mandala deejay, equal in diameter to our Brahmanda, has a diameter of 500 million yojanas (trad. 8 miles each), which equals effectually 4 billion miles or more than, a size far besides minor for the universe of stars and galaxies, but in the right range for our solar system. In addition, the Bhagavata Purana and other Puranas speak of a multiplicity of universes, or Brahmandas, each covered by seven-fold layers with an aggregate thickness of over 10 million times its diameter (5x10fifteen yojanas ≈ half dozen,804+ calorie-free-years in diameter). The Jyotisha Shastras, Surya Siddhanta, and Siddhānta Shiromani give the Brahmanda an enlarged radius of well-nigh v,000 calorie-free years. Finally, the Mahabharata refers to stars every bit big, cocky-luminous objects that seem modest because of their great altitude, and that our Sun and Moon cannot exist seen if 1 travels to those distant stars. Thompson notes that Bhu-mandala can exist interpreted as a map of the geocentric orbits of the sun and the five planets, Mercury through Saturn, and this map becomes highly accurate if we adjust the length of the yojana to virtually viii.five miles.[71]

Brahma, the first born and secondary creator, during the starting time of his kalpa, divides the Brahmanda (catholic egg or universe), kickoff into three, afterward into xiv lokas (planes or realms)—sometimes grouped into heavenly, earthly and hellish planes—and creates the first living entities to multiply and fill the universe. Some Puranas describe innumerable universes existing simultaneously with different sizes and Brahmas, each manifesting and unmanifesting at the same time.

Indian philosophy [edit]

The Samkhya texts country that there are two distinct fundamental eternal entities: the Purusha and the Prakriti. The Prakriti has three qualities: sattva (purity or preservation), rajas (cosmos) and tamas (darkness or destruction). When the equilibrium between these qualities is broken, the act of creation starts. Rajas quality leads to creation.[72]

Advaita Vedanta states that the creation arises from Brahman, but information technology is illusory and has no reality.[l] : 103

Cycles of creation and destruction [edit]

Many Hindu texts mention the wheel of cosmos and destruction.[50] : 104 Co-ordinate to the Upanishads, the universe and the World, along with humans and other creatures, undergo repeated cycles of creation and destruction (pralaya). A diversity of myths be regarding the specifics of the procedure, just in general the Hindu view of the cosmos is as eternal and cyclic. The later puranic view also asserts that the universe is created, destroyed, and re-created in an eternally repetitive series of cycles. In Hindu cosmology, age of earth is about 4,320,000,000 years (i day of Brahma that is 1000 times of sum of four yugas in years, the creator or kalpa)[73] and is and so destroyed by fire or water elements. At this signal, Brahma rests for 1 dark, just equally long as the solar day. This process, chosen pralaya (cataclysm), repeats for 100 Brahma years (311 trillion, twoscore billion human years) that represents Brahma's lifespan.

Lokas [edit]

Deborah Soifer describes the development of the concept of lokas as follows:

The concept of a loka or lokas develops in the Vedic literature. Influenced by the special connotations that a discussion for space might have for a nomadic people, loka in the Veda did not simply hateful place or earth, but had a positive valuation: information technology was a identify or position of religious or psychological involvement with a special value of function of its own. Hence, inherent in the 'loka' concept in the earliest literature was a double aspect; that is, coexistent with spatiality was a religious or soteriological meaning, which could exist independent of a spatial notion, an 'immaterial' significance. The virtually common cosmological conception of lokas in the Veda was that of the trailokya or triple globe: iii worlds consisting of earth, atmosphere or sky, and heaven, making up the universe.

—Deborah A. Soiver[74]

Upper 7 Lokas in Hindu Cosmology

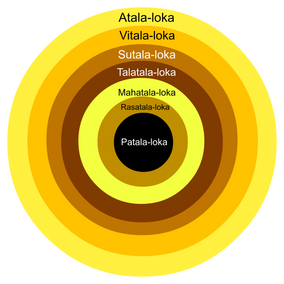

Lower 7 Lokas in Puranas

In the Brahmanda Purana, as well every bit Bhagavata Purana (2.5),[75] xiv lokas (planes) are described, consist of seven higher (Vyahrtis) and seven lower (Patalas) lokas.[76] [77]

- Satya-loka (Brahma-loka)

- Tapa-loka

- Jana-loka

- Mahar-loka

- Svar-loka (Svarga-loka or Indra-loka)

- Bhuvar-loka (Sun/Moon plane)

- Bhu-loka (Earth airplane)

- Atala-loka

- Vitala-loka

- Sutala-loka

- Talatala-loka

- Mahatala-loka

- Rasatala-loka

- Patala-loka

Withal, other Puranas requite different version of this cosmology and associated myths.[78]

Multiple universes [edit]

The Hindu texts describe innumerable universes existing all at the same time moving around similar atoms, each with its ain Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva.

Every universe is covered by vii layers—earth, water, burn, air, sky, the full free energy and faux ego—each ten times greater than the previous one. At that place are innumerable universes likewise this one, and although they are unlimitedly large, they move almost like atoms in You. Therefore You are called unlimited.

Considering Y'all are unlimited, neither the lords of heaven nor even You lot Yourself can e'er achieve the finish of Your glories. The countless universes, each enveloped in its shell, are compelled by the bicycle of time to wander inside Y'all, like particles of dust bravado near in the sky. The śrutis, following their method of eliminating everything separate from the Supreme, get successful past revealing Y'all every bit their final decision.

The layers or elements covering the universes are each ten times thicker than the one before, and all the universes clustered together appear similar atoms in a huge combination.

And who will search through the wide infinities of space to count the universes adjacent, each containing its Brahma, its Vishnu, its Shiva? Who can count the Indras in them all--those Indras next, who reign at once in all the innumerable worlds; those others who passed away before them; or even the Indras who succeed each other in any given line, ascending to godly kingship, one by 1, and, one by 1, passing abroad.

Every matter that is any where, is produced from and subsists in infinite. It is always all in all things, which are contained every bit particles in it. Such is the pure vacuous infinite of the Divine agreement, that like an ocean of light, contains these innumerable worlds, which similar the countless waves of the bounding main, are revolving for ever in information technology.

At that place are many other large worlds, rolling through the immense infinite of vacuum, as the featherbrained goblins of Yakshas revel about in the dark and dismal deserts and forests, unseen by others.

You know ane universe. Living entities are built-in in many universes, like mosquitoes in many udumbara (cluster fig) fruits.

Run into also [edit]

- Brahmapura

- Hindu calendar

- Hindu creationism

- Hindu eschatology

- Hindu idealism

- Hindu units of time

- Indian astronomy

- Loka

- Patala

- Puranic chronology

- Urthva lokas

- Vaikuntha

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b In Bhagavad Gita Lord Krishna says "Air, h2o, earth, fire, heaven, mind, intelligence and ahankaar (ego) together constitute the nature created by me."

- ^ देवानां नु वयं जाना पर वोचाम विपन्यया

References [edit]

- ^ a b James G. Lochtefeld, Guna, in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-Yard, Vol. ane, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, pages 224, 265, 520

- ^ Alban Widgery (1930), The principles of Hindu Ethics, International Periodical of Ethics, Vol. 40, No. 2, pages 234–237

- ^ a b Theos Bernard (1999), Hindu Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1373-1, pages 74–76

- ^ Axel Michaels (2003), Notions of Nature in Traditional Hinduism, Environment across Cultures, Springer, ISBN 978-3-642-07324-three, pages 111–121

- ^ Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad-Gita, a New Translation and Commentary, Chapter 1–vi. Penguin Books, 1969, p 128 (5 45) and p 269 five.xiii

- ^ Prakriti: Indian philosophy, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ "Mahattattva, Mahat-tattva: five definitions". Wisdom Library . Retrieved x February 2021.

Mahattattva (महत्तत्त्व) or merely Mahat refers to a primordial principle of the nature of both pradhāna and puruṣa, according to the 10th century Saurapurāṇa: ane of the various Upapurāṇas depicting Śaivism.—[...] From the disturbed prakṛti and the puruṣa sprang upward the seed of mahat, which is of the nature of both pradhāna and puruṣa. The mahattattva is then covered by the pradhāna and being so covered it differentiates itself equally the sāttvika, rājasa and tāmasa-mahat. The pradhāna covers the mahat just as a seed is covered past the skin. Being then covered there spring from the iii fold mahat the threefold ahaṃkāra chosen vaikārika, taijasa and bhūtādi or tāmasa.

- ^ David Bruce Hughes. Sri Vedanta-sutra, Adhyaya 2. David Bruce Hughes. p. 76.

- ^ Swami Sivananda - commentator (1999). Brahma Sutras. Islamic Books. pp. 190–196.

- ^ Elankumaran, Due south (2004). "Personality, organizational climate and job involvement: An empirical study". Journal of Human Values. 10 (2): 117–130. doi:10.1177/097168580401000205. S2CID 145066724.

- ^ Deshpande, S; Nagendra, H. R.; Nagarathna, R (2009). "A randomized command trial of the effect of yoga on Gunas (personality) and Self esteem in normal healthy volunteers". International Journal of Yoga. 2 (ane): thirteen–21. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.43287. PMC3017961. PMID 21234210.

- ^ Shilpa, South; Venkatesha Murthy, C. Chiliad. (2011). "Understanding personality from Ayurvedic perspective for psychological cess: A example". Ayu. 32 (one): 12–19. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.85716. PMC3215408. PMID 22131752.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). G.South. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Data and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 79.

- ^ Prasad Sinha, Harendra (2006). Bharatiya Darshan Ki Rooprekha. Motilal Banarsidass Publisher. p. 86. ISBN9788120821446 . Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "PANCHA BHOOTAS OR THE V ELEMENTS". indianscriptures.com/ . Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Sushil Mittal, Gene Thursby (2012). Hindu Globe. Routledge. p. 284. ISBN9781134608751.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Andrew Zimmerman Jones (2009). String Theory For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 262. ISBN9780470595848.

- ^ Teresi 2002, p. 174.

- ^ "yuga". Dictionary.com Entire (Online). n.d. Retrieved 27 Feb 2021.

- ^ Sundarraj, M. (1997) [1st ed. 1994]. "Ch. 4 Asvins—Fourth dimension-Keepers". In Mahalingam, N. (ed.). RG Vedic Studies. Coimbatore: Rukmani First Printing. p. 219.

Information technology is quite clear that the smallest unit of measurement was the 'nimisah' ['winking of eyes'], and that time in the general sense of past, present and futurity was indicated past the give-and-take 'yuga'.

- ^ González-Reimann 2018, p. 415 (World Destruction and Re-creation).

- ^ Doniger, Wendy; Hawley, John Stratton, eds. (1999). "Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Globe Religions". Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. p. 691 (Manu). ISBN0877790442.

a day in the life of Brahma is divided into 14 periods called manvantaras ("Manu intervals"), each of which lasts for 306,720,000 years. In every second bike [(new kalpa after pralaya)] the world is recreated, and a new Manu appears to become the male parent of the next human race. The present age is considered to be the 7th Manu bicycle.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, V. (2019). "Ch. 20: The Catholic Flow of Fourth dimension as per Scriptures". Meet the Aboriginal Scriptures of Hinduism. Notion Press. ISBN9781684669387.

Each manvantara is preceded and followed by a period of 1,728,000 (= 4K) years when the entire earthly universe (bhu-loka) will submerge nether h2o. The period of this deluge is known every bit manvantara-sandhya (sandhya meaning, twilight). ... According to the traditional fourth dimension-keeping ... Thus in Brahma's calendar the present time may be coded equally his 51st year - first month - starting time twenty-four hour period - 7th manvantara - 28th maha-yuga - 4th yuga or kaliyuga.

- ^ Gupta, S. V. (2010). "Ch. 1.2.4 Fourth dimension Measurements". In Hull, Robert; Osgood, Jr., Richard M.; Parisi, Jurgen; Warlimont, Hans (eds.). Units of Measurement: By, Present and Future. International System of Units. Springer Series in Materials Science: 122. Springer. pp. 7–8. ISBN9783642007378.

- ^ Penprase, Bryan E. (2017). The Power of Stars (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 182. ISBN9783319525976.

- ^ Johnson, Due west.J. (2009). A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. p. 165. ISBN978-0-xix-861025-0.

- ^ Graham Chapman; Thackwray Driver (2002). Timescales and Environmental Change. Routledge. pp. 7–8. ISBN978-i-134-78754-8.

- ^ Ludo Rocher (1986). The Purāṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 123–125, 130–132. ISBN978-3-447-02522-5.

- ^ John E. Mitchiner (2000). Traditions of the Seven Rsis. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 141–144. ISBN978-81-208-1324-iii.

- ^ Johnson, W. J., 1951- (12 February 2009). A lexicon of Hinduism (First ed.). Oxford [England]. ISBN9780198610250. OCLC 244416793.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary'south Press. ISBN978-0-88489-725-5.

- ^ Krishna, the Beautiful Legend of God, pages 11–12, and commentary pages 423–424, by Edwin Bryant

- ^ Teun Goudriaan (2008), Maya: Divine And Human, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120823891, pages 4, 167

- ^ Richard 50. Thompson (2003), Maya: The Globe equally Virtual Reality, ISBN 9780963530905

- ^ Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 272. ISBN978-1-4522-6656-5.

- ^ Jeaneane D. Fowler (1997). Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN978-1-898723-60-8.

- ^ Christopher Chapple (1986), Karma and creativity, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-88706-251-two, pages 60–64

- ^ Flood, Gavin (24 August 2009). "Hindu concepts". BBC Online. BBC. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ George D. Chryssides; Benjamin E. Zeller (2014). The Bloomsbury Companion to New Religious Movements. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 333. ISBN978-1-4411-9829-7.

- ^ Georgis, Faris (2010). Solitary in Unity: Torments of an Iraqi God-Seeker in North America. Dorrance Publishing. p. 62. ISBN978-1-4349-0951-0.

- ^ "How did the world come into being according to Hinduism?".

- ^ Robert Thou. Torrance (1 April 1999). Encompassing Nature: A Sourcebook. Counterpoint Press. pp. 121–122. ISBN978-1-58243-009-6 . Retrieved xv December 2012.

- ^ Henry White Wallis (1887). The Cosmology of the Ṛigveda: An Essay. Williams and Norgate. pp. 61–73.

- ^ a b Jan North. Bremmer (2007). The Strange World of Human Sacrifice. Peeters Publishers. pp. 170–. ISBN978-90-429-1843-half dozen . Retrieved 15 Dec 2012.

- ^ Charles Lanman, To the unknown god, Volume X, Hymn 121, Rigveda, The Sacred Books of the East Volume IX: India and Brahmanism, Editor: Max Muller, Oxford, pages 49–50

- ^ a b Edward Quinn (one Jan 2009). Critical Companion to George Orwell. Infobase Publishing. p. 188. ISBN978-1-4381-0873-5 . Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ a b Southward. North. Sadasivan (one January 2000). A Social History Of India. APH Publishing. pp. 226–227. ISBN978-81-7648-170-0 . Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ "Rig Veda: Rig-Veda, Book x: HYMN Ninety. Puruṣa". Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Worlds Together Worlds Apart", Fourth Edition, Beginnings Through the 15th century, Tignor, 2014, pg. 5

- ^ a b c d e f thou h i j Roshen Dalal (five October 2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. pp. 318–319. ISBN978-0-14-341421-half dozen . Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Griffith, Ralph T.H. (Transl.): Rigveda Hymn CXXIX. Creation in Hymns of the Rgveda, Vol. Ii, 1889-92. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, 1999.

- ^ Charles Lanman, The Creation Hymn, Book X, Hymn 129, Rigveda, The Sacred Books of the Eastward Book Nine: Republic of india and Brahmanism, Editor: Max Muller, Oxford, page 48

- ^ Patrick McNamara; Wesley J. Wildman (19 July 2012). Scientific discipline and the Globe's Religions [three Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 180–. ISBN978-0-313-38732-half dozen . Retrieved 15 Dec 2012.

- ^ a b Jamison, Stephanie; Brereton, Joel (2014). The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 1499–1500, 1607–1609. ISBN9780199370184.

- ^ Kenneth Kramer (January 1986). World Scriptures: An Introduction to Comparative Religions. Paulist Press. p. 34. ISBN978-0-8091-2781-8.

- ^ David Christian (1 September 2011). Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. University of California Printing. p. 18. ISBN978-0-520-95067-2.

- ^ Robert Northward. Bellah (2011). Religion in Human Evolution. Harvard University Printing. pp. 510–511. ISBN978-0-674-06309-ix.

- ^ Dark-brown, W. Norman (1942). "The Creation Myth of the Rig Veda". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 62 (ii): 85–98. doi:10.2307/594460. JSTOR 594460.

- ^ Charles Lanman, Hymns past Women, Volume X, Hymn 125, Rigveda, The Sacred Books of the Due east Volume IX: India and Brahmanism, Editor: Max Muller, Oxford, pages 46–47

- ^ Rig Veda 10.72 translation by R.T.H. Griffith (1896)

- ^ Henry White Wallis (1887). The Cosmology of the Ṛigveda: An Essay. Williams and Norgate. p. 117.

- ^ Laurie L. Patton (2005). Bringing the Gods to Mind: Mantra and Ritual in Early Indian Cede. University of California Press. pp. 113, 216. ISBN978-0-520-93088-ix.

- ^ Merry I. White; Susan Pollak (2 November 2010). The Cultural Transition: Man Experience and Social Transformation in the Third Earth and Japan. Edited by Merry I White, Susan Pollak. Taylor & Francis. p. 183. ISBN978-0-415-58826-3 . Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Sunil Sehgal (1999). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism: C-G. Sarup & Sons. p. 401. ISBN978-81-7625-064-one . Retrieved fifteen December 2012.

- ^ F. Max Muller (thirty June 2004). The Upanishads, Vol I. Kessinger Publishing. p. 228. ISBN978-1-4191-8641-7 . Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Fourth Brâhmana in Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Quaternary Brahmana. Translated by Max Müller every bit The Upanishads, Part 2 (SBE15) [1879].

- ^ Due south.K. Paul, A.N. Prasad (1 Nov 2007). Reassessing British Literature: Pt. ane. Sarup & Sons. p. 91. ISBN978-81-7625-764-0 . Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Mircea Eliade; Charles J. Adams (1987). The Encyclopedia of religion . Macmillan. pp. 100–113, 116–117. ISBN978-0-02-909730-four.

- ^ Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Civilization in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 151–155 (Matsya Purana and other examples). ISBN978-0-19-971825-2.

- ^ Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Artful Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 259–262. ISBN978-three-11-024003-0.

- ^ Thompson, Richard L. (2007). The Cosmology of the Bhāgavata Purāna: Mysteries of the Sacred Universe. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 239. ISBN978-81-208-1919-1.

- ^ Dinkar Joshi (1 January 2005). Glimpses Of Indian Culture. Star Publications. p. 32. ISBN978-81-7650-190-three . Retrieved fifteen December 2012.

- ^ A survey of Hinduism, Klaus M. Klostermaier, 2007, pp. 495-496

- ^ Soiver, Deborah A. (November 1991). The Myths of Narasimha and Vamana: Two Avatars in Cosmological Perspective. State University of New York Press. p. 51. ISBN978-0-7914-0799-8.

- ^ Barbara A. Holdrege (2015). Bhakti and Embodiment: Fashioning Divine Bodies and Devotional Bodies in Krsna Bhakti. Routledge. p. 334, note 62. ISBN978-i-317-66910-4.

- ^ John A. Grimes (1996). A Curtailed Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English language. Land University of New York Press. p. 95. ISBN978-0-7914-3067-v.

- ^ Ganga Ram Garg (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu Earth. Concept. p. 446. ISBN978-81-7022-375-7.

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 83. ISBN978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ Bryan E. Penprase (5 May 2017). The Ability of Stars. Springer. p. 137. ISBN9783319525976.

- ^ Mirabello, Mark (15 September 2016). A Traveler's Guide to the Afterlife: Traditions and Beliefs on Death, Dying, and What Lies Beyond. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 23. ISBN9781620555989.

- ^ Amir Muzur, Hans-Martin Sass (2012). Fritz Jahr and the Foundations of Global Bioethics: The Time to come of Integrative Bioethics. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 348. ISBN9783643901125.

- ^ Ravi M. Gupta, Kenneth R. Valpey (29 Nov 2016). The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition. Columbia University Press. p. 60. ISBN9780231542340.

- ^ Thompson 2007, p. 200.

- ^ Joseph Lewis Henderson, Maud Oakes (4 September 1990). The Wisdom of the Snake: The Myths of Death, Rebirth, and Resurrection. Princeton University Press. p. 86. ISBN0691020647.

- ^ Yoga Vasistha

- ^ Yoga Vasistha

- ^ Garga Samhita (59)

Bibliography [edit]

- Bodewitz, Henk (2019). "The Hindu Doctrine of Transmigration: Its Origin and Groundwork". In Heilijgers, Dory; Houben, Jan; van Kooij, Karel (eds.). Vedic Cosmology and Ethics: Selected Studies. Gonda Indological Studies. Vol. nineteen. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 3–20. doi:10.1163/9789004400139_002. ISBN978-90-04-39864-one. JSTOR10.1163/j.ctvrxk42v.6. S2CID 203303894.

- Overflowing, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge Academy Press, ISBN9780521438780

- González-Reimann, Luis (2018). "Cosmic Cycles, Cosmology, and Cosmography". In Basu, Helene; Jacobsen, Knut A.; Malinar, Angelika; Narayanan, Vasudha (eds.). Brill'southward Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. ii. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:x.1163/2212-5019_BEH_COM_1020020. ISBN978-90-04-17641-6. ISSN 2212-5019.

- Haug, Martin (1863). The Aitareya Brahmanam of the Rigveda, Containing the Earliest Speculations of the Brahmans on the Significant of the Sacrificial Prayers. ISBN 0-404-57848-9.

- Joseph, George G. (2000). The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics, 2nd edition. Penguin Books, London. ISBN 0-691-00659-eight.

- Kak, Subhash C. (2000). 'Birth and Early Development of Indian Astronomy'. In Selin, Helaine (2000). Astronomy Beyond Cultures: The History of Not-Western Astronomy (303–340). Boston: Kluwer. ISBN 0-7923-6363-ix.

- Teresi, Dick (2002). Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science — from the Babylonians to the Maya. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc. ISBN0-684-83718-eight.

External links [edit]

- Ancient Hindu Astronomy

- The Àryabhatiya of Àryabhata: The oldest verbal astronomical abiding?

- Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 8 verse 17

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_cosmology

0 Response to "Do I Have to Again Take Birth After the Universe Is Recreated"

Post a Comment